The Silent Adjustments: Existing as a Woman in STEM

The Unspoken Weight of Being One of the Few

When I first set foot in STEM, I thought the hardest part would be the coursework—the long hours, the technical rigour, the problem sets that kept me up at night.

I was wrong.

The hardest part wasn’t the material. It was the feeling that I had to prove, over and over again, that I belonged there at all.

Before I pursued a double major in Mechanical Engineering and Innovation Design at the National University of Singapore, where I spent my time working on payload research for cube satellites, I was a physics major—one of only four women in my entire cohort.

And that meant I was hyper-aware of everything—how I spoke, how I dressed, how I carried myself. Because whether I wanted to or not, I wasn’t just representing myself—I was representing every woman who came after me.

Too Pretty to Be an Engineer? Too Girly to Be Taken Seriously?

"You look too feminine to be an engineer."

"You don’t look or dress like a physicist.”

“Why aren’t you in the Faculty of Arts?”

I remember hearing that and thinking—since when did being feminine disqualify someone from being competent?

But in STEM, there’s an unspoken dress code for credibility.

If you wear makeup, if your clothes are too stylish, if you don’t look like you rolled out of bed straight into the lab, people start to question you.

So I adjusted.

Dressed in hoodies and plain outfits.

→ Because the less attention I drew to my appearance, the more people would focus on my work.

Lowered my pitch when I spoke.

→ Because sounding more masculine meant being taken more seriously.

Bro-zoned my entire cohort.

→ Because if you’re seen as a potential romantic partner instead of a colleague, suddenly your ideas matter less.

The goal was simple: blend in just enough to avoid being dismissed.

The Day I Realised I Would Always Have to Justify My Presence

I will never forget my first-ever engineering internship application.

I had the credentials—a double STEM major, a project on CubeSat payloads, and hands-on technical experience. I had just completed my first module on spacecraft systems design. I was even tutoring O-Level physics at the time.

I was ready to talk about all of it. I even made sure to highlight it in my email and cover letter.

The hiring manager asked a few questions about my interest in the space industry. I spent time carefully drafting my responses, explaining and justifying my passion for space. Back-and-forth emails. More explanations.

I was puzzled. I thought I had already told him everything that needed to be said.

Then, it clicked.

The moment I received this email:

"I think there is enough on your CV to suggest what you’re capable of doing. What is perplexing is that you have been involved in the arts. This makes your interest in astrophysics and space unclear."

Not impressive. Perplexing.

Because when men have diverse interests, they are multifaceted. When women do, they are inconsistent.

A man who loves physics and music is a Renaissance thinker. A woman who does the same is a contradiction.

But here’s what makes that comment even more absurd:

Some of the greatest minds in physics were also artists, musicians, and creatives.

Albert Einstein played the violin and credited music for shaping his scientific thinking.

Richard Feynman, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist, was also an accomplished painter and bongo player.

Max Planck, the father of quantum theory, was a talented pianist and composer.

Erwin Schrödinger, known for his famous thought experiment, was a philosopher and poet.

Niels Bohr, one of the pioneers of quantum mechanics, had a deep appreciation for literature and drama.

Not one of them had to explain why their love for the arts coexisted with their brilliance in physics.

Because at the highest levels of science, creativity isn’t just accepted—it’s essential.

But when a woman has a creative background? It becomes a red flag. A reason to question whether she belongs.

This is how women in STEM get pushed out without anyone ever saying it outright—not through direct exclusion, but through constant scrutiny. Through these subtle, persistent signals that whisper: Are you sure you belong here?

So, I dropped that company.

But I learned my lesson.

From that point on, I made sure to never mention anything creative or have any association to the arts in professional settings.

Because I had seen firsthand how one word—"arts"—could erase years of technical expertise in an instant.

The Pressure of Carrying Every Woman on Your Back

When you’re one of the only women in the room, you don’t just carry your own success or failure—you carry the weight of proving that women belong in the room at all.

Every mistake didn’t feel like my mistake. It felt like proof—proof to someone, somewhere, that maybe women in STEM really weren’t as good as men.

So I worked harder. I held myself to an impossible standard.

Even when I succeeded, imposter syndrome whispered:

Maybe I just got lucky.

Maybe they’re right—maybe I don’t belong here.

Maybe I’ll make one mistake and they’ll finally see I was never meant to be here in the first place.

And when I wasn’t doubting myself, others did it for me.

"Women belong in the kitchen."

→ Said as ‘harmless banter’ by male classmates in my physics cohort, casually reinforcing the idea that women didn’t belong in STEM.

"Who would you ‘shoot, shag, marry’ among the four physics girls in our entire cohort?"

→ A group of male physicists at a post-exam gathering, openly ranking and commenting on our physical appearance—right in front of me and the only other girl there.

"My hobby is objectifying women."

→ A male classmate said this to me, completely seriously. Minutes later, he was ogling female engineers walking by, loudly commenting on how "f***ing hot"** they were—like we weren’t even people, just something to be rated.

We were discussing an astronomy event in a mass cohort chat. I said, ‘The moon is really round.’

→ A batchmate I barely knew publicly tagged me and replied: "Like your boobs."

And that was just one example of the many instances I was publicly sexualised without shame, without hesitation, and without consequence.

There was no outrage. No pushback. Just silence and smirks—because in that space, this wasn’t shocking or unacceptable. It was normal.

I eventually left the group when I pursued engineering. And even then, long after I had forgotten about the misogyny I faced there, it found its way back to me.

I had left that world behind. But it hadn’t left me.

A friend sent me a screenshot from the same mass cohort chat—two years after I had switched majors.

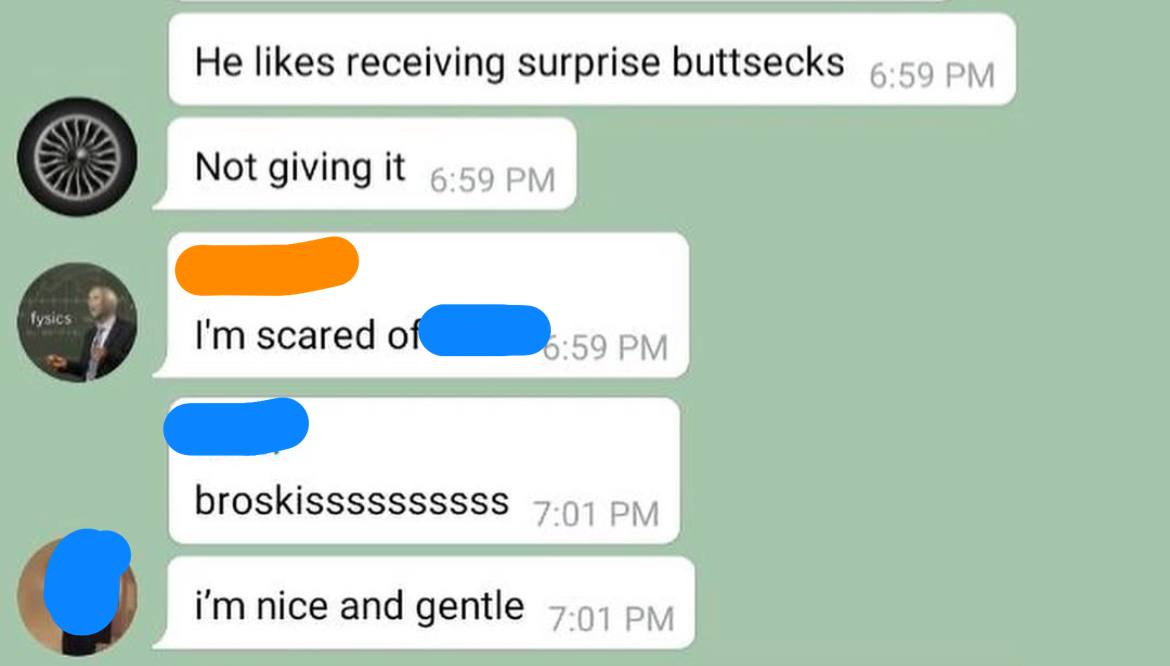

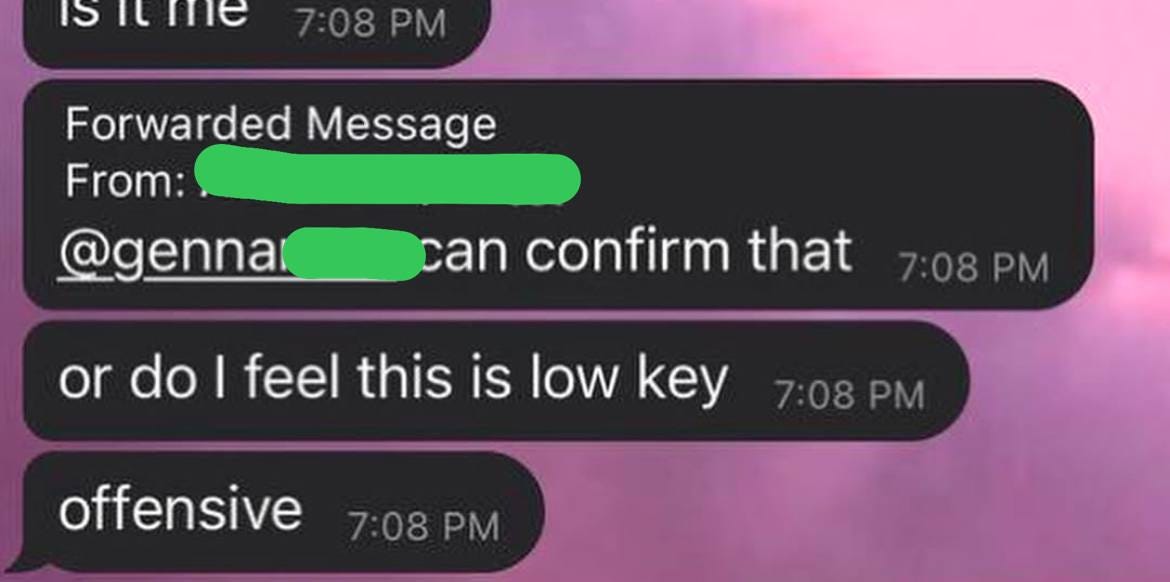

Guy A: “I’m nice and gentle.”

[They were joking about sex.]

His buddy: “Genna can confirm that.”

→ I wasn’t even in the group. I hadn’t spoken to them in years. But they still felt entitled to drag my name into their jokes.

People laughed along. No one said a thing. And when I called it out? I couldn’t take a joke.

These weren’t just classmates. They were two years older, men who had already served in the military.

Too Friendly? The First Time I Realised Networking Was Different for Women

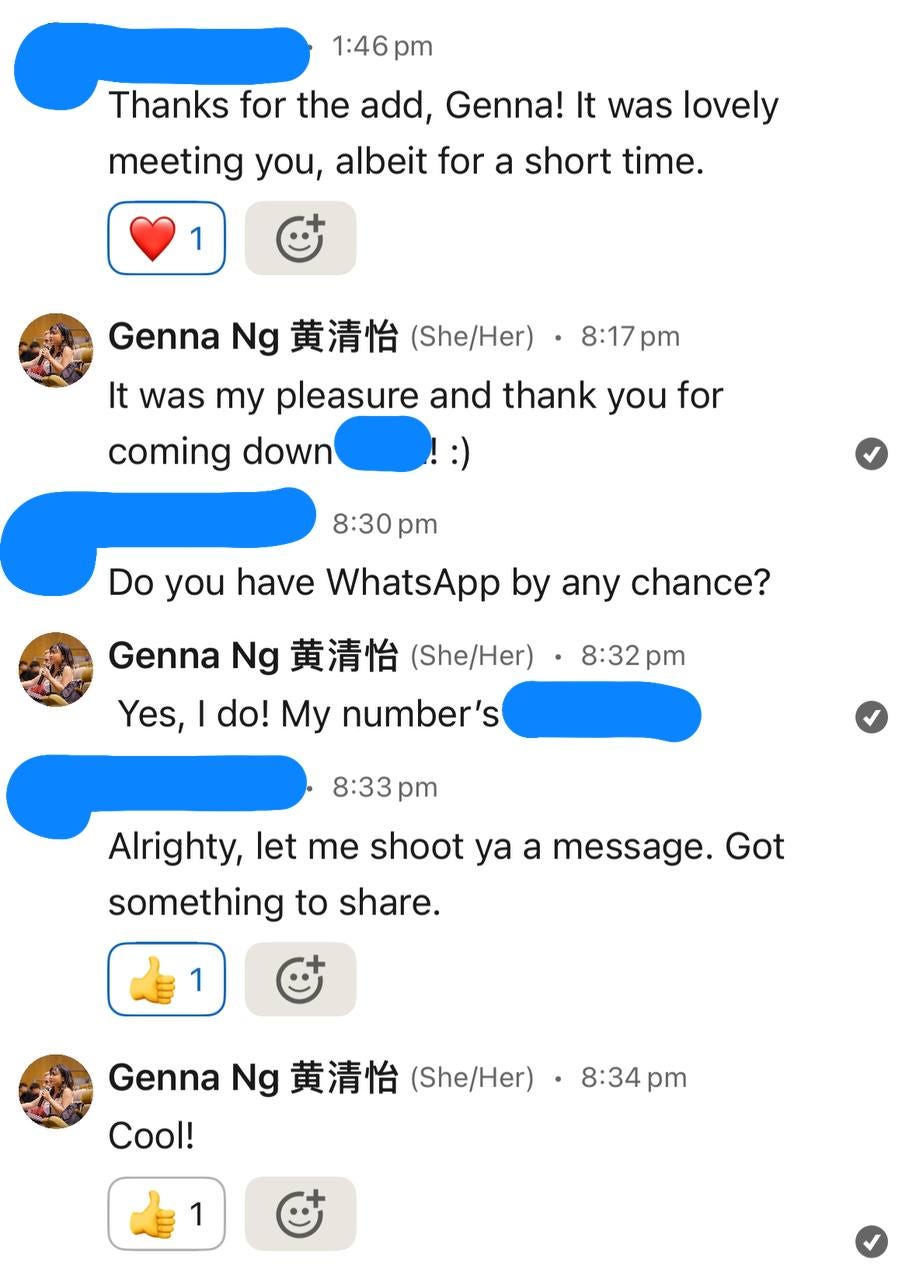

I was new to the working world, excited that someone in the industry wanted to talk about my work outside of a formal setting.

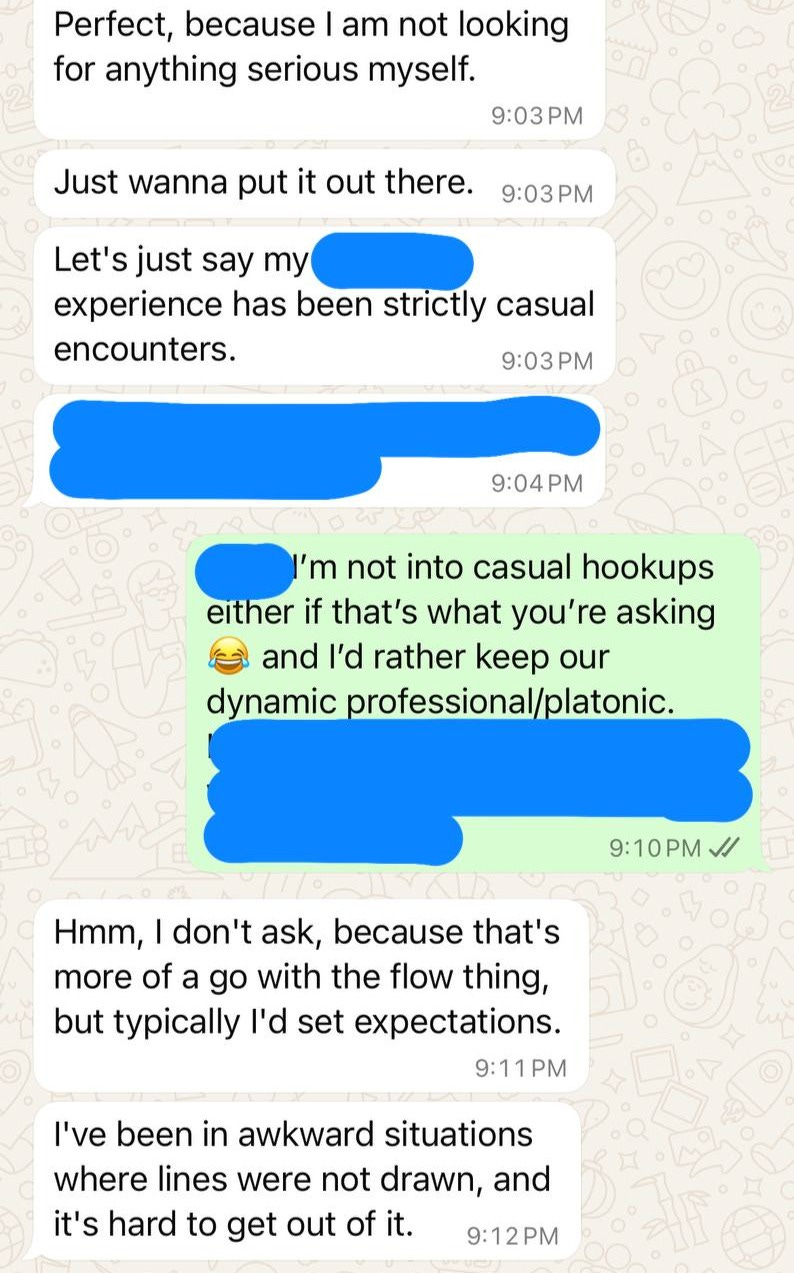

A guy from the industry reached out on LinkedIn, and wanted to talk to me over WhatsApp.

At first, it seemed like just that—a professional conversation.

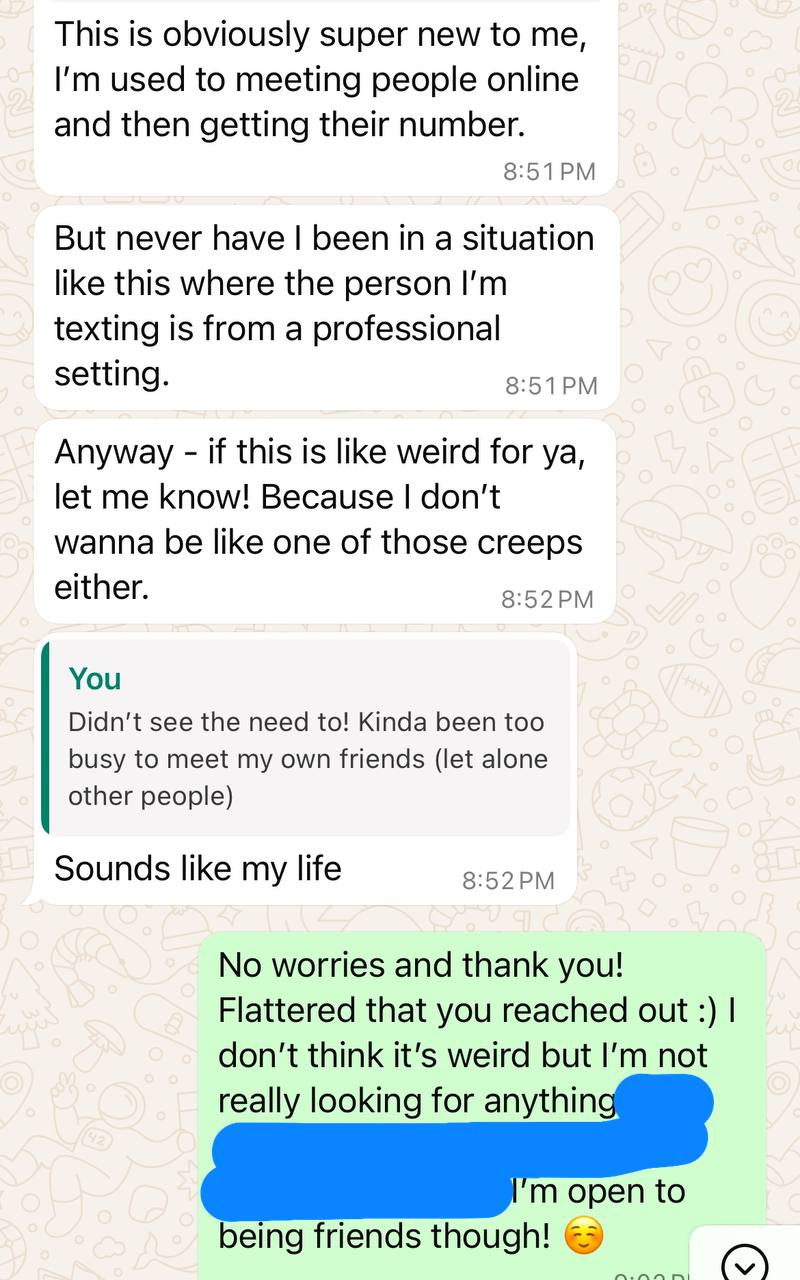

And then, at some point, the tone shifted.

It wasn’t about my work anymore.

Suddenly, he was dropping hints, making suggestions, steering the conversation somewhere I wasn’t expecting. It didn’t take long before it became clear that he wasn’t interested in my ideas at all—he was trying to hook up with me.

And the worst part? His company was a potential client.

I was cautious. I couldn’t just offend him outright. I had to navigate the situation carefully, trying to shut it down without risking professional consequences.

I stayed polite. I made it clear I wasn’t interested.

But he persisted.

Even after rejecting him multiple times, he kept pushing—acting as if I’d eventually change my mind.

(I later found out he had a fiancée)

And that’s what stuck with me the most. The assumption that his persistence would wear me down. That my “no” wasn’t really a no.

I had always known things like this happened to women in professional spaces, but I guess some part of me had hoped that my environment was different—that because we were all here for the same intellectual curiosity, the same drive to innovate, the same hunger to build, I wouldn’t have to deal with this.

But that’s the difference—a guy can walk into a networking conversation expecting to be taken seriously from the start. A woman walks in and has to second-guess the entire interaction.

Unlearning the Lesson

For a long time, I thought the solution was to make myself smaller.

To be careful. To be calculated. To avoid giving anyone a reason to question my competence, my seriousness, my place in the room.

So I adjusted. I downplayed. I shrank parts of myself.

And it worked.

But at what cost?

Looking back now, I’m not sure if the world changed, or if I simply learned to move through it differently.

Because as I stepped into bigger rooms, worked on real projects, and surrounded myself with the right people, I stopped being questioned like that.

I found myself among cool, forward-thinking minds—the kind of people who understood that creativity and technical excellence aren’t contradictions. That having dimension doesn’t make you weaker—it makes you better.

And when I finally started mentioning my creative side again?

No one batted an eye.

Turns out, the problem was never me.

It was the small-mindedness of those who couldn’t see beyond their own rigid boxes.

But here’s what I know now: I was lucky.

Because for every woman who makes it through, there are countless others still walking that tightrope. Still second-guessing whether their voice is too high, their dress too polished, their presence too noticeable. Still doing the silent calculus of every interaction—because they’ve seen what happens when you get it wrong.

I know that feeling too well. I’ve gone down my fair share of imposter syndrome rabbit holes, searching for reassurance that I wasn’t alone. And thankfully, I wasn’t.

I found articles, forums, and videos that helped me put words to what I was experiencing.

To name a few:

Yes, Sexual Harassment Still Drives Women Out of Physics by Julie Libarkin

This TED talk by Debbie Sterling:

Stories from women in STEM, and research on imposter syndrome—each one a small lifeline that reminded me that I wasn’t imagining things.

And if you’ve ever felt the same way, I hope this article does that for you.

Because the next generation of women in STEM shouldn’t have to walk on eggshells just to be taken seriously.

They shouldn’t have to dull their personality, their style, their humanity, just to make it easier for other people to fit them into a box.

The goal was never just inclusion.

It was to exist—fully, unapologetically, without negotiation.